Translate this page into:

Splenic Artery Pseudoaneurysm—A Concern for the Anesthesiologist

Neeti Makhija, MD Department of Cardiac Anaesthesia & Critical Care Room No. 9, 7th Floor, Cardiothoracic Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110029 India neetimakhija@hotmail.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Pseudoaneurysms as compared with aneurysms lack a true wall and have a higher propensity of rupture. Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms are uncommon and are life-threatening. We, hereby, report anesthetic management of a rare case of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm that accompanied the dilatation of aorta from its origin extending up to its bifurcation.

Keywords

anesthetic management

pseudoaneurysms

splenic artery

Introduction

Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms are uncommon and can be life-threatening. Visceral artery pseudoaneurysms are a result of trauma, infection, vasculitis, inflammation, prior surgery, interventional procedures, and pancreatitis.1 Pseudoaneurysms lack a true wall and have a higher risk of rupture as compared with true aneurysms.2 Therefore, even in asymptomatic patients either surgical or endovascular treatment should be undertaken promptly.

We report a rare case of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm and its management. Traditional surgical treatments such as bypassing, excision, or ligature and resection of the end-organ have been used for many years.3 In the recent years, endovascular treatment options like coil embolization, Gelfoam, thrombin injection, stent-graft implantation, or a combination of these techniques have been offered for treating visceral artery aneurysms.4

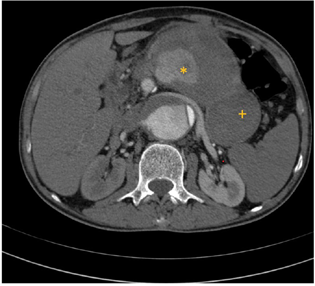

A 53-year-old male, weighing 54 kg, presented in emergency with a history of abdominal pain for the last 1 month. Patient was a known case of aortic aneurysm with fusiform dilatation of aorta from its origin extending up to bifurcation with dilatation of celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery, and bilateral common iliac artery. However, the recent computed tomography angiography revealed a large splenic artery pseudoaneurysm with peripheral thrombus (Fig. 1). Patient's hemoglobin was 6.2 g% and was transfused two units of packed red blood cells (PRBC) in the emergency department. In view of splenic pseudoaneurysm (contained rupture), the decision for urgent embolization was taken.

- Computed tomography angiography axial image showing splenic artery pseudoaneurysm (*) with peripheral thrombus (+).

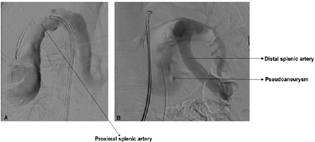

Patient was taken up in catheterization laboratory for emergency endovascular management of splenic artery pseudoaneurysm with vascular surgical team and perfusionist on standby. Two large-bore intravenous (IV) cannula each of 16 G were placed. A 20 G catheter in left radial artery for invasive arterial pressure monitoring and 8.5 Fr triple lumen central venous catheter in right internal jugular vein were placed under local anesthesia. Percutaneous femoral artery access with 6 Fr sheath was taken bilaterally under local anesthesia for endovascular procedure. Patient had pulse rate of 85/min, noninvasive blood pressure was 176/80 mm Hg and oxygen saturation of 100% with oxygen at 6L/min via nonrebreathing mask. Blood pressure was managed with inj nitroglycerin infusion 0.5 to 2 µg/kg/min. Vasopressor in form of inj noradrenaline infusion was kept ready. Selective celiac angiogram showed large pseudoaneurysm of splenic artery with antegrade flow in distal splenic artery (Fig. 2). The usual strategy of embolization is to close backdoor first followed by front door.

- Digital subtraction angiography images: (A) Lateral oblique and (B) anteroposterior projection showing origin of pseudoaneurysm from splenic artery.

The distal splenic artery was selectively catheterized distal to the pseudoaneurysm and was embolized using multiple micro coils, followed by deployment of Amplatzer vascular plug-II of 18 mm diameter into the proximal splenic artery that is considered the front door (Fig. 3). No periprocedural complication occurred. Check angiogram showed complete exclusion of pseudoaneurysm. Definitive repair of aortic aneurysm was planned electively. Patient was transfused one-unit PRBC intraoperatively

- Check digital subtraction angiography showing coils (+) and plug (*) in distal and proximal portion of splenic artery, respectively, with complete exclusion of pseudoaneurysm.

Splenic artery is the third most common site of intraabdominal aneurysm after aneurysm of the abdominal aorta and the iliac arteries. Patients with visceral artery aneurysm may have extensive comorbidities and therefore require careful preoperative assessment. These patients are at high risk of acute kidney injury postoperatively due to use of IV contrast, increasing age, complexity of the procedure, perioperative dehydration, as well as medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aminoglycosides, and diuretics in the perioperative period. Possibility of sudden collapse due to rupture of pseudoaneurysm may mandate immediate cardiorespiratory management.5

Large-bore IV access is very important in such patients because of the risk of bleeding. Invasive arterial pressure monitoring helps in continuous monitoring of blood pressure and early diagnosis of hemodynamic instability. A 5-lead electrocardiogram helps to detect ischemic ST changes.5 Adequate number of PRBCs should be available in hand in the procedure room.

Endovascular treatment of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms is usually conducted under local anesthetic infiltration with sedation.6 Immediate control of hypertension is easily managed with nitrates and/or short-acting beta-blockers. Hypotension is managed with vasopressors (noradrenaline, phenylephrine). Most of the patients are administered 5000 IU of IV heparin after the cannulation of the access vessel. Activated clotting time should be maintained at 2 to 2.5 times the baseline (∼200–250 seconds).5

Anesthetic preparation should be performed with the awareness that there is a risk of major hemorrhage and conversion to an open procedure can occur at any stage. Good teamwork and communication are essential when performing endovascular procedures and this is even more vital during emergency cases. A comprehensive understanding of these procedures is essential to provide a high level of anesthetic care and maintain patient safety.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Splenic artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms: clinical distinctions and CT appearances. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(4):992-999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of visceral artery aneurysms: description of a retrospective series of 42 aneurysms in 34 patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 2004;18(6):695-703.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdominal and pelvic aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms: imaging review with clinical, radiologic, and treatment correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33(3):E71-E96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multimodal approach to endovascular treatment of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59(1):104-111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anesthetic considerations for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Card Anaesth. 2016;19(1):132-141.

- [Google Scholar]

- The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(2):276-283. , discussion 283

- [Google Scholar]