Translate this page into:

Role of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in the Diagnosis of Cardiac Amyloidosis

Fabiola B Sozzi, MD, PhD Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Via F. Sforza 35, Milano 20122 Italy fabiola_sozzi@yahoo.it

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Cardiac amyloidosis (CA) is characterized by progressive pathological deposition of amyloid fibrils in the myocardial interstitium, resulting ultimately in restrictive cardiomyopathy. The amyloid fibrils accumulating in the heart are most commonly misfolded immunoglobulin light chains (in case of AL amyloidosis) or transthyretin (ATTR), the latter being either in wild-type or variant conformation.

Overall, heart involvement is one of the strongest predictors of poor prognosis, with a median survival after diagnosis that ranges from less than 12 months for AL amyloidosis to 3–5 years for ATTR amyloidosis.1 Therefore, early detection and phenotyping of CA are crucial to stratify prognosis and guide treatment.

In the last decade, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) and bone scintigraphy have led to a major breakthrough in the accuracy of diagnosis of CA.

CMR allows detailed evaluation of structural and functional changes related to each stage of CA, from asymptomatic occasional finding to advanced heart failure.

The pathological deposition of amyloid fibrils results in biventricular wall thickening and preserved ejection fraction (EF), at least until late. However, the systolic function of the heart is abnormal. Since the early stages of the disease, global longitudinal strain is characteristically reduced for both the left ventricle and right ventricle, sparing the apical segments, with a so-called “apical sparing” pattern.2 The indexed stroke volume may be reduced. The decrease in EF is commonly seen in the advanced stage of the disease and is invariably associated with heart failure and poor survival rate, especially in case of AL amyloidosis.

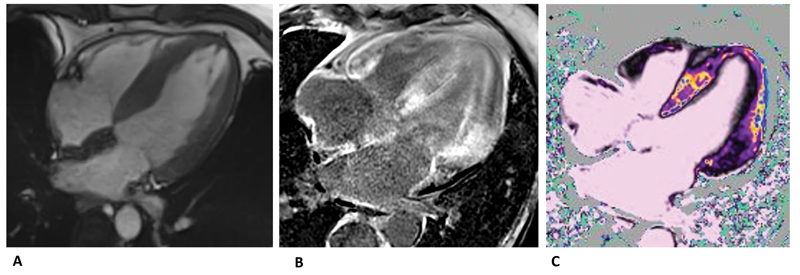

The infiltration of amyloid proteins can also involve the atria, the interatrial septum, and atrioventricular valves causing hypertrophy (Fig. 1A). Recently, a high prevalence of ATTR in patients with severe calcific aortic stenosis has been reported and a pathophysiological association has been hypothesized.3

- (A) SSFP four-chamber view showing left ventricular and left atrial hypertrophy. (B) Late-gadolinium enhancement distributed in both septum and atrium-ventricular walls.(C) T1-mapping native significantly elevated compatible with fibrosis. SSFP, steady state free precession.

CMR is able to detect all the previously mentioned structural abnormalities and provides a comprehensive evaluation of the systolic function of the heart. However, diastolic function is not formally assessed.

The key advantage of CMR in CA is its unique ability to give information about the tissue composition by “myocardial tissue characterization,” both with and without administration of gadolinium.

After the administration of contrast, in case of massive interstitial expansion due to amyloid, it could be difficult or even impossible to null the myocardium according to the late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) technique. This is an almost pathognomonic sign for CA. With a phase sensitive inversion recovery approach, three patterns of LGE could be present: none, subendocardial, or transmural. The subendocardial distribution is typically “tram-line,” involving both the ventricles, especially the basal segments, not following coronary artery distribution territories. Along with the progression of amyloid deposition, a transmural pattern of LGE can be seen. This is associated with a fivefold increase in mortality compared with patients with CA without LGE.4 In the most advanced stages, pan-myocardial LGE has been described (Fig. 1B).

Due to the high prevalence of severe chronic kidney disease in patients with systemic amyloidosis, a great interest has grown in native T1-mapping, which allows tissue characterization without administration of contrast.5 Along with the expansion of the interstitial space due to amyloid accumulation, native T1-mapping and extracellular volume (ECV)-mapping are significantly elevated in patients with CA (Fig. 1C). This sign is very specific and correlates with prognosis. Moreover, elevated T1-mapping and ECV-mapping could be found also in the absence or ill-defined LGE, thus acting as a potential early marker of disease.

In conclusion, CMR is fundamental for the diagnosis of CA. Its specificity and accuracy paid the way to the development of algorithms for a definitive diagnosis of CA without the need of biopsy. However, despite scores based on difference in the pattern of LGE have been proposed (QALE [quality adjusted life expectancy] score reference), it is still not possible to characterize the type of amyloid deposition based on CMR findings.

Therefore, clinical suspicion and expertise are needed to integrate the information derived from imaging into the clinical setting for the care of patients with CA.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- How to image cardiac amyloidosis: a practical approach. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(6):1368-1383.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transthyretin amyloidosis in aortic stenosis: clinical and therapeutic implications. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2021;23:E128-E132. (Suppl E):

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2015;132(16):1570-1579.

- [Google Scholar]

- T1 mapping and survival in systemic light-chain amyloidosis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(4):244-251.

- [Google Scholar]