Translate this page into:

Phenytoin-Induced Cardiac Conduction Abnormalities

Glen Brown, PharmD, FCSHP, BCPS, BCCCP Pharmacy Department, St. Paul’s Hospital 1081 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia V6Z 1Y6 Canada gbrown@providencehealth.bc.ca

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Pvt. Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Phenytoin possesses electrophysiological effects consistent with those of the Vaughan–Williams 1B classification. As such, phenytoin may widen the QRS complex but would not be expected to result in QTc prolongation or ST elevation. The reported case demonstrates these unexpected electrophysiological effects with supratherapeutic concentrations of phenytoin when no other potential cause could be elucidated. No contributing factors present in the case, compared with previously published reports of electrophysiological effects of supratherapeutic phenytoin concentrations, could be elucidated. The report suggests that clinicians should monitor for potential conduction abnormalities in patients with elevated phenytoin concentrations.

Keywords

phenytoin

QTc prolongation

overdose

Introduction

The electrophysiological effects of phenytoin consist predominantly of accelerating repolarization of myocardial fibers, resulting in shortening of the action potential duration and effective refractory period, predominantly in the ventricles.1 These characteristics are consistent with the effects of Vaughan–Williams class IB antiarrhythmics.2 Phenytoin has minimal effect on conduction velocity within normal His–Purkinje fibers and, as a result, is not expected to produce prolongation of the QT interval or alteration in the morphology of the QRS complex.2 Even toxic concentrations of phenytoin, which are documented following inadvertent or intentional overdoses, have not resulted in noticeable changes in the QRS or QT duration or the QT morphology.3, 4 Reports of impairment of atrioventricular (AV) node conduction resulting in heart block are available but have only been reported following rapid infusion of intravenous (IV) phenytoin.5 The following case describes diffuse prolongation in the QT duration accompanied by dramatic changes in the QRS morphology, occurring concurrently with excessively elevated concentrations of phenytoin.

Case Report

A mature, adult male was found in his residence with decreased level of consciousness and low arterial oxygenation saturation, as measured by pulse oximetry. Prior to his transportation to the emergency department, he responded partially to the administration of naloxone. Upon arrival, he was witnessed to have a single tonic–clonic seizure lasting 8 minutes that terminated following the administration of lorazepam 2 mg given three times over 15 minutes. Subsequently, he was intubated for airway protection and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for ongoing decreased level of consciousness. Four hours following ICU admission, he underwent a lumbar puncture, which demonstrated 1 × 106/L white blood cells and a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein concentration of 0.65 g/L. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head demonstrated no pathological changes. Gram stain, bacterial cultures, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of CSF were negative for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus. He received an IV phenytoin loading dose of 900 mg over 60 minutes (weight = 56 kg) as prophylaxis for any further seizures. A maintenance dose of 300 mg IV every 24 hours was initiated, which was changed to 100 mg IV every 8 hours on day 2. An electroencephalogram (EEG) at 12 hours following admission was suggestive of rhythmic runs of generalized epileptiform discharges, which prompted the initiation of a propofol infusion to provide sedations equivalent to a Richmond Agitation and Sedation Score of–5. A repeat EEG on day 4 following admission without propofol suggested persistent frequent epileptiform discharges.

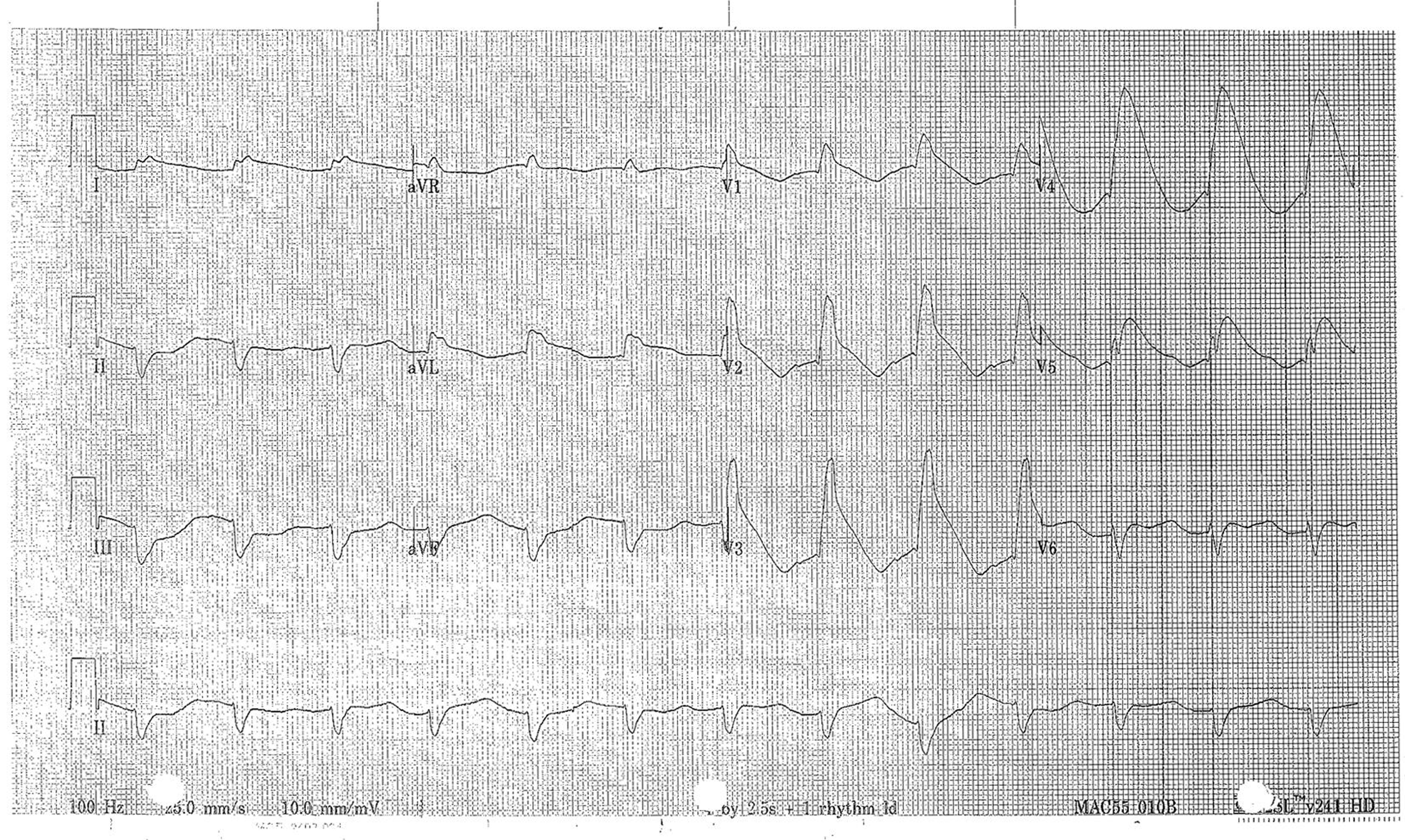

The electrocardiogram upon admission following phenytoin loading dose was normal except for a prolonged QT interval of 412 ms, with a QTc of 545 ms. Magnesium sulfate therapy of 20 mmol (5 g) was administered on each of day 1 through day 3. On day 3, the QT/QTc had increased to 488/570 ms. However, on day 5, the QT/QTc was 612/692 ms demonstrating profound, diffuse ST elevation (Fig. 1). A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated regional wall motion abnormalities including hypokinesis of the anterior septum, inferior septum, posterior wall, and midanterior segments. The serum troponin concentration on day 5 was 38 ng/L (normal range: <14 ng/L), down from 240 ng/L on day 1. An urgent coronary angiogram was performed but demonstrated no evidence of coronary artery disease.

- Electrocardiogram from day 5 demonstrating diffuse ST elevation and QTc prolongation

With the normal coronary angiogram, phenytoin was subsequently considered as a possible cause for the ECG changes and was discontinued on day 5 at 14:00 hours. By day 8, the QT/QTc was 324/451 ms with no evidence of any ST elevation. Despite extensive investigations, no other cause of QT prolongation was identified. Concurrent medications at the time included acyclovir, ipratropium, levetiracetam, multivitamins, pantoprazole, and salbutamol. All of these, except acyclovir, were continued through day 8. From day 4 through day 8, serum magnesium concentrations were between 0.98 and 1.39 mmol/L (normal: 0.75–1.05 mmol/L) and potassium concentrations remained between 3.7 and 5.0 mmol/L (normal: 3.6–5.0 mmol/L).

Over the initial 5 days of admission, only total phenytoin serum concentrations were measured (Table 1). The initial corrected concentration on day 1 would not be anticipated to reflect a high free phenytoin concentration since the serum albumin was greater than that on the subsequent days when conduction abnormalities were prominent. On days 7 and 8, total and free phenytoin concentrations were measured to better characterize the potential role of excessive phenytoin. From day 6 through day 8, the phenytoin concentrations declined and the QT/QTc concurrently declined, returning to a normal QT/QTc (324/451 ms) by day 8.

|

Day |

Total phenytoin (umol/L) |

Free phenytoina (umol/L) |

Serum albumin (g/L) |

Corrected phenytoinb (umol/L) |

Estimated Free phenytoinb,c (umol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

aRecommended “therapeutic range: = 4–8 umol/L. bEstimated correction for serum albumin: corrected concentration = measured/(0.9(serum albumin/44)+0.1). cBased on the mean percentage: free/total from day 7 and 8 measurements. |

|||||

|

Day 1: random |

70 |

21 |

132 |

||

|

Day 4, a.m.: trough |

34 |

15 |

84 |

7.3 |

|

|

Day 4, p.m.: trough |

52 |

13 |

142 |

11.2 |

|

|

Day 6, a.m.: random |

81 |

26 |

128 |

17.4 |

|

|

Day 7, a.m.: random |

69 |

15.9 |

24 |

117 |

|

|

Day 8, a.m.: random |

44 |

8.6 |

24 |

74 |

|

|

Day 11, a.m.: random |

<4 |

19 |

Incalculable |

||

The patient’s neurologic status improved over the subsequent days, with an EEG on day 8 demonstrating no clinical or subclinical seizures. He recovered from his illness, although no cause was determined for his initial seizures.

Discussion

The case illustrates diffuse changes in the QT interval and QRS morphology associated with phenytoin toxicity. Other potential etiologies, including cardiac ischemia, raised intracranial pressure, other medications, or electrolyte abnormalities, were excluded. Although the delayed (5–288 hours postictally) development of Takotsubo’s syndrome following epileptic seizures has been reported,6 the electrocardiogram changes reported are not similar to this case. Thus, Takotsubo’s syndrome was not thought to be the cause. The electrocardiographic changes normalized concurrently with the decrease in the phenytoin concentration and did not reoccur at a later time. The absence of coronary artery obstruction and the lack of serum troponin elevation ruled out the presence of cardiac ischemia as a potential cause. Any potential effect of phenytoin on altering conduction during cardiac ischemia would not be contributory.2The Naranjo classification of this event would be “probable adverse drug reaction” as defined from a score of 7 points based on appearing after drug was started (2 points), improvement with discontinuation (1 point), no alternate explanation evident (2 points), presence of toxic concentrations (1 point), and reduction in severity with dose reduction (1 point).7

Phenytoin has been reported to result in a Brugada pattern electrocardiogram.8, 9 Phenytoin has sodium channel blocking activities that are associated with the development of Brugada syndrome. However, Vaughan–Williams class 1B agents, such as phenytoin, are not frequently associated with Brugada’s syndrome. The sodium channel blocking effects of phenytoin may result in widening of the QRS complex due to slowing of the inward sodium flow during the action potential, but this would not be associated with QTc prolongation or ST elevation.10 The pathophysiological mechanism for the induced conduction pattern in our case is unknown.

It appears that the detrimental cardiac electrophysiological effects of phenytoin, unrelated to the rate of IV administration, appear only with supratherapeutic concentrations.4, 8, 9 Outside the setting of rapid IV administration, the occurrence of cardiac conduction abnormalities appears very rare. Wyte and Berk reported lack of new-onset cardiac conduction disturbances (QRS widening or QT prolongation) in 57 patients with supratherapeutic concentrations following oral ingestion. The total serum peak concentrations had a mean of 49 mcg/mL (194 umol/L), with two patients having total concentrations of 70 to 79 mcg/mL (278–313 umol/L). Free phenytoin concentrations or albumin concentrations were not reported as being measured. Similarly, Evers et al reported on 44 patients with supratherapeutic phenytoin concentrations following oral administration. The mean total phenytoin concentration was 36 mcg/mL (145 umol/L), ranging from 20 mcg/mL (79 umol/L) to 75 mcg/mL (276 umol/L). They found no difference in the QRS or QT duration from the time of peak phenytoin concentration versus subsequent measurement at the time of discharge when phenytoin concentrations had declined and no clinical signs or symptoms of phenytoin toxicity were present.4 At the time of the conduction disturbances in our case, the highest total serum phenytoin concentration measured was 81 umol/L, which would be less than those found in the majority of cases by Wyte and Berk and by Evers et al. To assess for potential interaction of other medications, toxins, or hypoalbuminemia, a free phenytoin concentration is recommended if toxicity is present.11 The highest free concentration measured was 15.9 umol/L, which is approximately twofold greater than the upper limits of the recommended concentrations for seizure control of 8 umol/L.11 Using the measured free and total concentration ratios, the highest free phenytoin concentration is estimated to be approximately 17 umol/L, which would be greater than a twofold magnitude above the recommended concentration range. Thus, our patient was at risk of toxicities not seen at therapeutic concentrations for seizure control. However, the explanation for the ECG findings in this case, but not in reports of similar or greater concentrations, is not evident.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest of any sort with the subject of this manuscript.

Funding No financial support was necessary for the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Electrophysiology and pharmacology of cardiac arrhythmias. VIII. Cardiac effects of diphenylhydantoin. B. Am Heart J. 1975;90(3):397-404.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiarrhythmic drugs: electrophysiological basis of their clinical usage. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;41(1):106-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severe oral phenytoin overdose does not cause cardiovascular morbidity. Ann Emerg Med. 1991;20(5):508-512.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complete atrioventricular block with ventricular asystole following infusion of intravenous phenytoin. J Electrocardiol. 1995;28(2):157-159.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immediate versus delayed detection of Takotsubo syndrome after epileptic seizures. J Neurol Sci. 2019;397:42-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

- [Google Scholar]

- Brugada pattern electrocardiogram associated with supratherapeutic phenytoin levels and the risk of sudden death. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30(5):713-715.

- [Google Scholar]

- Type 1 Brugada pattern ECG due to supra-therapeutic phenytoin level. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016214899.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic drug monitoring of phenytoin in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(11):1391-1400.

- [Google Scholar]