Translate this page into:

ECMO in Poisoning

Vivek Gupta, MD Department of Cardiac Anaesthesia and Intensive care Hero DMC Heart Institute, Tagore Nagar, Ludhiana, Punjab 141001 India dr_vivekg@yahoo.com

This article was originally published by Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers Private Ltd. and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Severe poisoning may lead to life-threatening situation or death due to cardiovascular dysfunction, arrhythmia, or cardiogenic shock. The poisoning substance varies in different parts of world; in the Western world, the drugs with cardiotoxic potential are more common, while pesticides and other household toxins are common in the rest of the world. However, most of these patients are relatively young and otherwise healthy irrespective of poisoning substances. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has regained interest in recent past and now its use is being explored for newer indications. The use of ECMO in poisoning has shown promising results as salvage therapy and can be used as bridge to recovery, antidote, and toxin removal with renal replacement therapy or transplant. The ECMO has been used in those poisoned patients who have persistent cardiogenic shock or refractory hypoxemia despite adequate supportive therapy. ECMO may be useful in providing adequate cardiac output and maintain tissue perfusion which helps in the redistribution of toxins from central circulation and facilitate the metabolism and excretion. However, the available literature is not sufficient and is based on case reports, case series, and retrospective cohort study. In spite of high mortality with severe poisoning and encouraging outcome with use of ECMO, it is an underutilized modality across the world. Though evidences suggest that early consideration of ECMO in severely poisoned patients with refractory cardiac arrest or hemodynamic compromise refractory to standard therapies may be beneficial, the right time to start ECMO in poisoned patients, criteria to start ECMO, and prognostication prior to initiation of ECMO is yet to be answered. Future studies and publications may address these issues, whereas the ELSO (Extracorporeal Life Support Organization) data registry may help in collecting global data on poisoning more effectively.

Keywords

ECMO

ECLS

ECPB

intoxication

poisoning

“All substances are poisons; there is none

that is not a poison;

“The right dose differentiates a poison

from a remedy”

Paracelsus

Introduction

Globally, acute poisoning with medications or other toxic substances is a common presentation to emergency department.1 Conventional supportive therapy and specific antidotes administration are usually effective but may not be sufficient in cases of cardiovascular collapse due to life-threatening overdoses. Children are usually the victim of accidental overdoses and symptoms are usually apparent immediately while adult intoxication is usually deliberate and present late to emergency department.2

Poisoning-associated deaths both due to accidental ingestion and ingestion for self-harm have increased in the last few years. More than 5,000 poisoned patients are visiting emergency departments every day across the United States and unintentional poisoning is a significant cause of mortality, even exceeding road traffic accidents as a cause of death in the younger and middle age group. The poisoning victims are usually young though toxic substances varies across the world.3, 4

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used successfully in children with respiratory and cardiopulmonary failure. However, its use in adults remained limited until recently when the Cambridge Society for the Application of Research (CSAR) trials’ other reports showed a favorable outcome during H1N1 pandemic.5 The use of ECMO has increased more than fourfold in the last decade.6 ECMO supports the failing heart and/or lung functions unresponsive to conventional management until a specific endpoint has been achieved.7 It is often considered as a bridge therapy, buying time until definitive therapy has been instituted. For example, a deteriorating patient with a myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock can be shifted for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or a patient with a massive pulmonary embolus can undergo thrombectomy with ECMO support.

The main cause of death in patients with acute poisoning is failure of various vital organs. Intubation and mechanical ventilation has shown dramatic improvement in survival of sedative-induced respiratory failure, which was the leading cause of death in the Western world. Similarly, toxin-induced acute renal failure has successfully been managed with renal replacement therapy (RRT). Even liver transplant in drug-induced fulminant liver failure is reported in selected cases. However, the use of mechanical circulatory support in cardiac failure due to acute intoxication is still a matter of debate.8 ECMO helps in maintaining tissue perfusion and oxygenation in acutely intoxicated patient until the drug or toxin is eliminated by the body’s natural metabolism and excretory processes or possibly RRT may be instituted to enhance the elimination.

Once a toxin enters the systemic circulation and is distributed in the tissues, the cardiovascular collapse may require temporary support of circulatory function. This helps in hepatic detoxification over time,9 while providing reliable tissue perfusion and allowing sufficient antidote circulation.10 The various modalities such as continuous cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR; manual or with a mechanical device), intraaortic balloon (IAB) counterpulsation, and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) has been used.11

The miniaturization of circuit, safe application of ECMO due to advancement of technology, and better outcome has allowed critical care specialists and emergency physicians to explore newer indications for use of ECMO in intensive care unit (ICU). However, ECMO has not been established as a rescue modality in acutely intoxicated patients with cardiovascular collapse or cardiac arrest. Even the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) guidelines and registry data do not address the use of ECMO in acute intoxication. This review focuses on the mortality associated with acute intoxication, difference in toxicology profile across the globe, available literature on use of extracorporeal life support (ECLS), and discusses the current practices.

Clinical Epidemiology

The poisoning substances can be broadly divided into three groups: chemicals used in agricultural and industries, medications and health care products, and biological poisons such as plant toxins and animal toxins. The toxicity of these poisoning substances ranges from mild symptoms to severe and life-threatening cardiovascular dysfunction. Poisoning may be intentional (suicidal, homicidal, misuse, or abuse) or unintentional (accidental, occupational, etc.).4 Usually, 85% of patients presenting with poisoning have minor toxic effect and usually do not require aggressive treatment. Intentional exposures have more severe effects and poor outcome for obvious reason.12

Worldwide, an estimated 3 million cases of pesticide poisoning occur every year, resulting in an excess of 250,000 deaths.13 Intentional and unintentional pesticide poisoning has been acknowledged as a serious problem in many agricultural communities of low- and middle-income countries, including China, India, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam.14

More than 400,000 victims die due to accident (both natural and unnatural) in India and acute poisoning contributes to 6.3% (~26,000) deaths every year. However, suicide due to acute intoxication leads to around 30,000 deaths every year.3 Pesticides are the most common substances used in the developing world for poisoning and is associated with high mortality.15, 16 However, the toxic profile is different in the Western world, and medications, especially cardiovascular medications, illegal drugs, and biologically active substances contribute mostly for cardiovascular collapse and death.3, 17 However, most of these poisoning victims irrespective of cause, method, type, or nation belong to relatively younger age group.3, 4, 18

Death due to Toxin-Induced Cardiovascular Shock

Severe poisoning may lead to hemodynamic instability or collapse, which is also associated with the deterioration of other organ functions such as respiratory arrest or depression, gas exchange abnormalities, convulsions, and electrolyte and acid-base disorders. These metabolic factors further deteriorate the cardiac function and may potentiate the toxicity. The immediate focus on managing the severely poisoned patient is to follow the resuscitation protocols— a prompt assessment and maintenance of compromised airway, supporting the breathing, and optimization of circulation. Poor respiratory efforts or inadequate ventilation may require short-term mechanical ventilatory support, till the toxin is reversed or metabolized.19 Optimization of blood pressure should be achieved initially with intravenous (IV) fluids boluses. Specific antidote administration may help to optimize blood pressure. Hypotension unresponsive to adequate fluid resuscitation may indicate the need of administration of vasopressor and inotropic agents depending on clinical presentation.20 The inotropic agents are proarrhythmic and may further enhance the cardiovascular toxicity. Antiarrhythmic administration for the management of arrhythmias associated with poisoning should be avoided due to proarrhythmic potential and negative inotropic effect of these drugs. It is prudent to correct the acidosis, hypokalemia, hypomagnesaemia, and hypoxia, which reduces the chance of arrhythmia.20 There is significant advancement in the management and improved outcome of toxin-induced cardiovascular shock in last three decades. This is contributed by improvement in bedside hemodynamic monitoring, better understanding of shock, and aggressive supportive therapy for hemodynamic optimization.21, 22 Still, the incidence of cardiovascular collapse in patients with acute intoxication is as high as 17%.23 Sudden cardiac death in a younger and otherwise healthy population is most likely due to poisoning.24 The onset of cardiovascular effects after poison ingestion is short and depends not only on ingested quantity but also on the severity of toxic profile and type of toxin as well.

Common Poisoning Substances with Cardiotoxic Potential

-

Drugs: The pathophysiology of drug-induced cardiotoxicity and hypotension include hypovolemia, depressed myocardial function, arrhythmias, and systemic vasodilatation. Mainly the acute toxic heart failure is due to systolic dysfunction secondary to reduced myocardial contractility.25 Cardiotoxic potential is not restricted to cardiovascular drugs only, the mortality remains higher in compounds having membrane stabilizing activity.26

-

With membrane stabilizing activity:

-

Antiarrhythmics (Vaughan Williams class I).

-

Beta-blockers (propranolol, acebutolol, nadoxolol, pindolol, etc.).

-

Dopamine and norepinephrine uptake inhibitors (bupropion).

-

Antiepileptics (phenytoin and carbamazepine).

-

Antimalarial agents (quinine and chloroquin).

-

Polycyclic antidepressants (imipramine, desipramine, amitriptyline, and doxepin).

-

Opioids (dextropropoxyphene).

-

Recreational agent (cocaine).

-

Amphetamine-like substances.

-

-

Other drugs:

-

Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine, nicardipine, verapamil, diltiazem, etc.).

-

Meprobamate.

-

Colchicine.

-

Cardiac glycosides (digoxin).

-

H1 antihistaminic.

-

Beta-blockers (without membrane stabilizing activity).

-

-

-

Pesticides:

-

Plant toxins:30, 31 The most severe form of plant toxins may produce complete heart block, bradyarrhythmia, tachyarrhythmia, or ventricular arrhythmia.

-

Aconite.

-

Taxus.

-

-

Others:

-

Carbon monoxide.32

-

Cyanide.

-

Role of ECMO in Poisoning

The standard indication of using ECMO is acute severe heart or lung failure unresponsive to optimal conventional therapy with high mortality risk. ECMO should be considered if the mortality risk is 50% and ECMO should be started in most circumstances at 80% mortality risk,33 which is similar for poisoned patients. Moreover, these patients are relatively young and otherwise healthy. One can expect a better outcome once the toxin is either metabolized or completely eliminated from the body. ECMO may be useful in providing adequate cardiac output and maintain tissue perfusion which helps in redistribution from central circulation and facilitate the metabolism and excretion of poison. ECMO supports both cardio respiratory function (venoarterial [VA] ECMO) and respiratory function alone (VV ECMO) for a longer duration depending on indication. It is primarily indicated in patients with such severe cardiovascular dysfunction or severe ventilation and/or oxygenation problems that they are unlikely to survive conventional therapies and mechanical ventilation.34 Toxins such as organic hydrocarbon (paint remover, thinner) on aspiration damages the lungs and leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) without circulatory compromise. There are no guidelines for the appropriate time for ECMO initiation in severely poisoned patients. The decision about initiation primarily depends on the clinical judgment. The available scoring system for classifying the poisoning patients has its own limitations due to its subjective nature; however, it may help to identify the most severe form of patients (Grade 3 and 4).35

Bridge to recovery: Toxic substances having potential for cardiotoxicity, where antidote is not available, may be fatal even with conventional support. VA ECMO can support the cardiac function in poisoned patients with severe cardiotoxicity who have severe left or right ventricular dysfunction, persistent life-threatening arrhythmias, or even cardiac arrest unresponsive to conventional management. Cardiovascular function starts recovering once the toxic substance is either metabolized or excreted from the body. The duration of ECMO support depends on several factors such as severity of toxicity and recovery of cardiac dysfunction, half-life of toxin, and organ dysfunction at the time of initiation of ECMO.36, 37 VA ECMO reduced cardiac oxygen consumption and provided both hemodynamic and respiratory support as a bridge to recovery.38 Patients who have toxin-induced ARDS while stable hemodynamically and who are unresponsive to high ventilatory support can be managed with VV ECMO till the recovery of gas exchange function of the lungs.39 Even in cases of multiple drug intoxication or unknown poisoning with cardiogenic shock, ECMO support can be beneficial.40

Bridge to antidote: ECMO can be helpful in life-threatening arrhythmia or cardiovascular collapse with those toxins which can be managed successfully with antidote but which is not available readily due to short shelf-life and cost. Digoxin-specific antibodies fragments (Fab) rapidly improves the digitalis-induced arrhythmias and cardiac toxicity. However, digoxin poisoning is uncommon and Fab fragments are expensive with limited shelf-life. Patient can be supported with ECMO until Fab is administered.41, 42

Bridge to Toxin Elimination with Renal Replacement Therapy

Acute salicylate intoxication has been managed successfully with dialysis, which help in substantial amount of salicylate removal.43 So far, around 142 dialyzable poisons have been identified.44

The decision about dialyzing the poison depends on the molecular weight, protein binding, and volume of distribution of the toxin. Large molecular weight medications are poorly dialyzed. Toxic substances which are highly protein bound are less available for removal through RRT. If the toxic substance has large volume of distribution, elimination of toxic substance will be prolonged because RRT will remove toxic substance from plasma space only. If the patient has hemodynamic instability in spite of adequate supportive therapy, VA ECMO may be considered to maintain the hemodynamics. The RRT may be added to ECMO circuit or may be started separately to eliminate the toxin.45 The various techniques used for toxin removal include dialysis, hemoperfusion, hemofiltration, and plasmapheresis with plasma exchange. The basic principle of dialysis involves diffusion through a semipermeable membrane, whereas in hemoperfusion the toxin is adsorbed on the adsorbent surface of dialyzer. The mechanism of hemofiltration is convection across the membrane. These therapies may be used as single or in combination. The plasmapheresis is used for acute poisoning with the toxins which are highly protein bound.46, 47 Continuous RRT (CRRT) and slow low-efficiency dialysis (SLED) are preferred over intermittent hemodialysis during ECMO. However, peritoneal dialysis is not suitable as it does not remove toxins effectively.

Bridge to transplant: Toxins with the potential of irreversible and rapid progression of pulmonary fibrosis can be supported with VV ECMO as a bridge to transplant when lung transplant is not possible immediately due to either unavailability of viable donor or waiting for toxin metabolism and clearance from the tissues.48 Even VA ECMO can be useful as a bridge to permanent assist device in patients with persistent cardiac failure.

Review of Literature

There are no randomized trials on the use of ECMO in patients with severe intoxication having refractory shock or having ARDS. So, the available evidences are basically few animal studies, case reports, case series, and case cohort studies. A cautious interpretation of results is indicated due to potential for bias.

Drug toxins: Most of the available literature is from the Western countries and describe the use of ECMO in acute drug intoxication. The experimental evidences with three different trials using lidocain,49 desipramine,50 and amitryptaline51 in dogs and swine, respectively, have shown better outcome with ECLS in comparison to the conventional treatment using fluid, vasopressor, inotropes, antiarrhythmic agents, etc. The major drawback about all three studies was that the animals were put on ECLS immediately after collapse and the duration of ECLS was short. This may not hold true in actual human intoxication because they are not supported with ECLS immediately and the duration of ECLS is longer. However, these results are promising and encourage the use of ECMO in refractory shock due to poisoning. The experiences in human subject include an observational cohort which shows better outcome in six patients with severe intoxication with profound shock who received VA ECMO as compared with use of ECMO for other indications. The toxic substances were chloroquine, a tricyclic antidepressant, propafenone, a sclerotic agent, and diuretics.52 In another cohort of 17 patients where ECLS was initiated for refractory cardiac arrest, VA ECMO was instituted in all patients and a stable ECLS was achieved in 14 patients. The survival was better in patients with shock due to poisoning (25%) while none survived in the cardiogenic shock group.53 A retrospective cohort analysis in two hospitals in France analyzed all poisoning patients presented to the hospital. There was statistically significant favorable outcome (86% vs. 48%) in severely intoxicated patients with refractory shock or cardiac arrest, who were managed with VA ECMO as compared with conventional management with fluid, vasopressors, and other supportive measures.54 However, due to small number of patients treated with VA ECMO in this cohort, the interpretation of results should be done carefully.

Besides this, there are several case reports of successful management of drug intoxication with refractory shock using ECMO. The acute intoxication of drugs which has been supported successfully with ECMO include flecainide,55, 56 an antiarrhythmic agent, β-blocker,57 calcium channel blockers,58 digoxin,10 tricyclic antidepressant,41, 59 buprioprion,60 methamphetamine,61 and mepivacaine, a local anesthetic.62 These included both adult and pediatric patients, all of them were supported with VA ECMO but the time of initiation of ECMO and duration of ECMO was different in different cases. Common complications similar to any case of VA ECMO were reported such as bleeding, hypotension, thromboembolism, or minor neurological events. There is always a chance of reporting and publication bias in case reports but recovery and survival in such a critical population definitely encourages the use of ECMO in poisoned patients with profound shock. In another case series of 17 patients, who were severely intoxicated with different cardiotoxic drugs including membrane stabilizing agents, nearly 90% patients were successfully weaned off from emergency cardiopulmonary bypass (ECPB), and 76% were discharged without significant cardiac and neurological dysfunction. A few of them required CPR before commencing ECPB and four patients required RRT during ECPB to manage acute kidney injury. Although there were certain complications such as bleeding, limb ischemia, and thrombus formation, the authors concluded that ECPB is safe and effective in the management of severely poisoned patients (Fig. 1).45

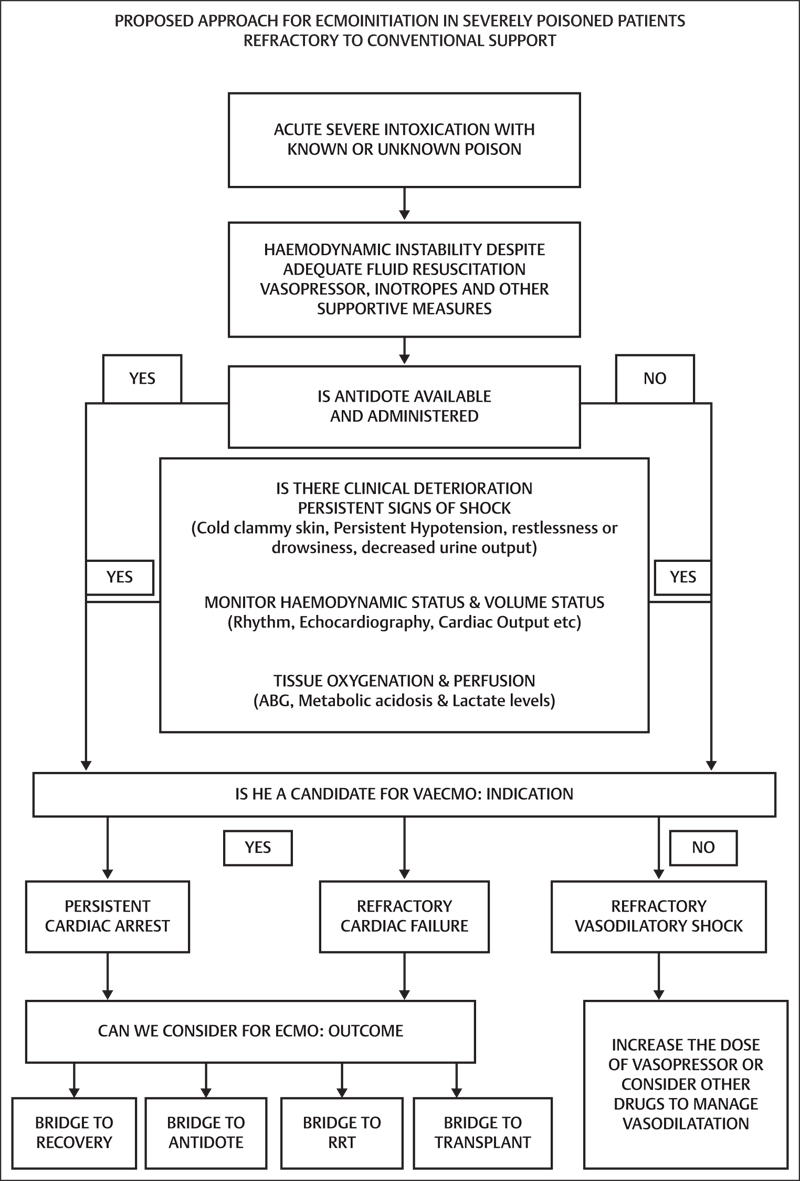

- Proposed approach for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) initiation in severely poisoned patients refractory to conventional support.

Other substances: The ECMO has not been used much in severe intoxication and refractory shock or severe ARDS with other toxic substances such pesticides, carbon monoxide, cyanide, and plant toxins. The available literature is restricted to case reports or case series with few patients only. These substances are commonly used as poison in the developing world with high mortality but ECMO is still not frequently available in this population. This may be a probable reason of underutilization of this modality. Carbon monoxide (CO) rapidly binds to hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin, leading to tissue hypoxia, multiple organ failure, and cardiovascular collapse. Both VV and VA ECMO may be used to manage tissue hypoxia depending on the hemodynamic stability.63 Aluminum phosphide, a deadly poison used as pesticide causing severe myocardial dysfunction, arrhythmia, and death, has been successfully managed with VA ECMO at different centres.29, 64, 65, 66 The plant toxin, Taxus-induced cardiogenic shock with ventricular arrhythmia has been successfully managed with VA ECMO.67 ARDS induced with organophosphorus poisoning has also been supported with VV ECMO.39 Even poison-induced lung fibrosis patient awaiting lung transplant is put on VV ECMO to improve gas exchange.48

Conclusion

The use of ECMO in acutely poisoned patients with refractory cardiogenic shock or refractory hypoxemia to conventional therapies is getting popular among the emergency physicians and intensivists as salvage therapy. However, ECMO is still an underutilized modality both in the developed and developing countries. The available evidences are limited to case reports and case series, which may have reporting and publication bias but randomized trial may be ethically unacceptable. Poisoning is a unique subject, not only because of huge number of toxic substances available but also since each substance has different pharmacological, metabolism, and elimination profile. It is understandable that ECMO may be helpful in supporting the hemodynamics irrespective of poisoning substances if cardiovascular dysfunction is unresponsive to standard therapies. The complications associated with ECMO may be life threatening and is minimized with expertise. Our understanding regarding the use of ECMO in poisoning is still limited and several issues are yet to be answered. This include the right time of ECMO initiation in acute intoxication, when to combine RRT to facilitate metabolic correction, cost-effective management, clarifications regarding the prognostic factors in poisoning prior to ECMO initiation, and decision regarding the withdrawal of ECMO support after improvement. All these issues may be addressed in future research and publications. However, ELSO, the largest world organization for ECMO data registry, may provide an excellent platform by encouraging global data collection on the ECMO use in poisoning. The decision regarding ECMO support in poisoning must be made carefully since ethical issues may arise in a situation of bridge to nowhere if the patient has developed irreversible organ damage.

References

- Management of deliberate self poisoning in adults in four teaching hospitals: descriptive study. BMJ. 1998;316:831-832. 7134

- [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Numbers of deaths from drug-related poisoning by underlying cause, England and Wales, 1998–2002. In: Census UK 2001. London: Office for National Statistics; 2001

- 49th Edition of the Report of National Crime Records Bureau, ‘Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India; 2015.’ http://ncrb.gov.in. Accessed December 12, 2017

- 2015 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 33rd annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54(10):924-1109.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critically Ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) in Mexico. JAMA. 2009;302(17):1880-1887.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use has increased by 433% in adults in the United States from 2006 to 2011. ASAIO J. 2015;61(1):31-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory failure: life support in the new era. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(2):210-220.

- [Google Scholar]

- TOX-ACLS: toxicologic-oriented advanced cardiac life support. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(4):S78-S90. Suppl

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful resuscitation of a verapamil-intoxicated patient with percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(12):2818-2823.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass for therapy resistant cardiac arrest from digoxin overdose. Resuscitation. 1998;37(1):47-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tricyclic antidepressant poisoning and prolonged external cardiac massage during asystole. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;283:1107-1108. 6299

- [Google Scholar]

- Intentional and unintentional poisoning in Pakistan: a pilot study using the Emergency Departments surveillance project. BMC Emerg Med. 2015;15:S2. Suppl 2

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute pesticide poisoning: a major global health problem. World Health Stat Q. 1990;43(3):139-144.

- [Google Scholar]

- International pesticide use. Introduction. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2001;7(4):259-265.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM. 2000;93(11):715-731.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early clinical outcome of acute poisoning cases treated in intensive care unit. Med Arh. 2015;69(6):400-404.

- [Google Scholar]

- Common causes of poisoning: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110(41):690-699, quiz 700.

- [Google Scholar]

- Occupational pesticide poisoning mortality, 2000-2009, Brazil [] Rev Saude Publica. 2013;47(3):598-606.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adult toxicology in critical care: Part II: specific poisonings. Chest. 2003;123(3):897-922.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jones AL, Dargan PI. Churchill’s Pocket Book of Toxicology. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2001

- Treatment of acute chloroquine poisoning: a 5-year experience. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(7):1189-1195.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in adults following drug overdose. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(7):843-849.

- [Google Scholar]

- Membrane stabilising activity: a major cause of fatal poisoning. Lancet. 1986;1:1414-1417. 8495

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac and electrocardiographical manifestations of acute organophosphate poisoning. Singapore Med J. 2004;45(8):385-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- Persistent left ventricular dysfunction in a teenager with yellow phosphorus poisoning. JCR. 2015;5:137-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fatal accidental aconitine poisoning following ingestion of Chinese herbal medicine: a report of two cases. Forensic Sci Int. 1994;67(1):55-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute plant poisoning: analysis of clinical features and circumstances of exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(7):671-680.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular effects of carbon monoxide poisoning. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(3):322-324.

- [Google Scholar]

- ELSO Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Extracorporeal Life Support. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, Version 1.4; August 2017. Ann Arbor, MI, USA. www.elso.org. Accessed December 12, 2017

- Poisoning severity score. Grading of acute poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36(3):205-213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and clinical course of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with carbon monoxide poisoning. Korean Circ J. 2016;46(5):665-671.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of aluminium phosphide poisoning by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;118(3):243-246.

- [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring of the adult patient on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Sci World J. 2014;2014:393258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a case of organophosphorus poisoning. Egypt J Crit Care Med. 2016;4:43-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extra-corporeal life support for near-fatal multi-drug intoxication: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011;5:231.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extra corporeal life support in life-threatening digoxin overdose: a bridge to antidote Austin. Emerg Med. 2016;2(5):1029.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digoxin-specific antibody fragments in the treatment of digoxin toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52(8):824-836.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acetylsalicylic acid intoxication; a proposed method of treatment. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;146(2):105-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of hemodialysis and hemoperfusion in poisoned patients. Kidney Int. 2008;74(10):1327-1334.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracorporeal life support in severe drug intoxication: a retrospective cohort study of seventeen cases. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amir AR, Winchester JF. Hemodialysis and hemoperfusion in the management of drug intoxication. In: Massry SG, Glassock RJ, eds. Massry & Glassock's Textbook of Nephrology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001:1729–1735

- Successful extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy as a bridge to sequential bilateral lung transplantation for a patient after severe paraquat poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015;53(9):908-913.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracorporeal pump assistance--novel treatment for acute lidocaine poisoning. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;22(2):129-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracorporeal life support vs thumper after lethal desipramine OD. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1990;32:349. (Abstract)

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental amitriptyline poisoning: treatment of severe cardiovascular toxicity with cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23(3):480-486.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous extracorporeal life support in acute severe hemodynamic collapses: single centre experience in 100 consecutive patients [in French] Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(6):e179-e186.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emergency feasibility in medical intensive care unit of extracorporeal life support for refractory cardiac arrest. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(5):758-764.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of survival with and without extracorporeal life support treatment for severe poisoning due to drug intoxication. Resuscitation. 2012;83(11):1413-1417.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracorporeal circulatory support in near-fatal flecainide overdose. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27(4):405-408.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful extracorporeal life support in a case of severe flecainide intoxication. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(4):887-890.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acebutolol overdose treated with hemodialysis and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36(8):760-763.

- [Google Scholar]

- Massive diltiazem overdose treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4(3):372-376.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for cardiac dysfunction from tricyclic antidepressant overdose. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(4):625-627.

- [Google Scholar]

- Refractory hypotension from massive bupropion overdose successfully treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(1):43-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laura KM, Kromm J, Gaudet J, et al Rescue extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in methamphetamine toxicity. CJEM 2017;31:1–6

- Michael F, Nikolaus AH, Guenther K, et al ECMO for cardiac rescue after accidental intravenous mepivacaine application. Case Rep Paediatr 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/491692

- Successful treatment of severe carbon monoxide poisoning and refractory shock using extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Respir Care. 2015;60(9):e155-e160.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severe reversible myocardial injury associated with aluminium phosphide toxicity: a case report and review of literature. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2014;26(4):216-221.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in aluminum phosphide poisoning-induced reversible myocardial dysfunction: a novel therapeutic modality. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(5):651-656.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of patients supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for aluminum phosphide poisoning: an observational study. Indian Heart J. 2016;68(3):295-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Suicide attempt with self-made Taxus baccata leaf capsules: survival following the application of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for ventricular arrhythmia and refractory cardiogenic shock. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(8):925-928.

- [Google Scholar]